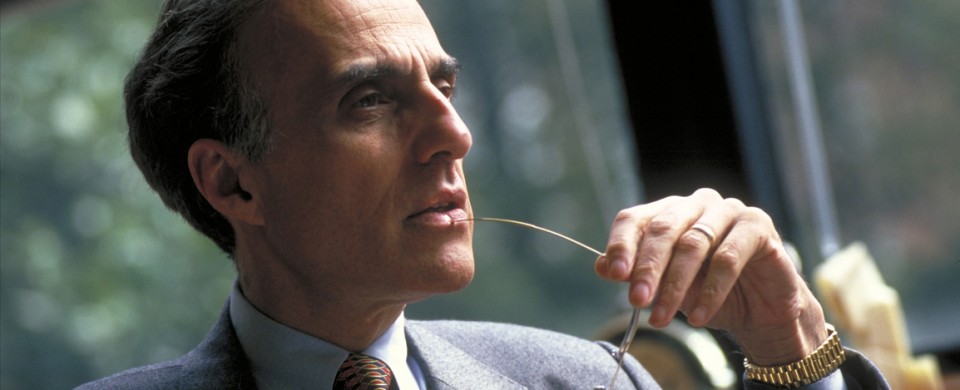

Esposito in Sarajevo: Dialogue without action is a waste of time

The capital of Bosnia and Herzegovina last week hosted John Louis Esposito, one of the leading international experts on Islam and an advocate of pluralism and dialogue between religions. He received an honorary doctoral degree from the University of Sarajevo and was the first lecturer at the Al-Wasatiyya Center for Dialogue. The university’s rector, Muharem Avdispahic, said, “By awarding him that honor, we, among other things, are responding to the recognition of the value and tradition in the practice of religious tolerance in Bosnia and Herzegovina that Professor Esposito has underscored in his work and numerous public addresses.”

In addition to giving special importance to becoming an honorary doctor at its oldest university, Esposito found Bosnia a favorable country — and “very close to me,” he said — for expressing his views on some fundamental issues of relations between and within the “Abrahamic religions.” Due to his intellectual and scholarly priority, he had Islam particularly in mind. Having attended all the events of his third visit to Sarajevo, I chose to share his following words that lead to core concerns regarding very accurate abuse of religious affiliation for political purposes in the Middle East and Muslim-majority countries:

“We can freely say that religion represents the positive and transcendental qualities and, as such, helps people to be better,” Esposito said last Friday at Sarajevo University, continuing: “However, the historical fact is that religion has had its dark side, which becomes dangerous if we connect it with the notions of society and politics. Religious leaders today have to work on reaching the true reinterpretation of their own values, respectively, in a way to help religion to confirm its best qualities. The Abrahamic religions and traditions should realize that it is about Judeo-Christian-Islamic tradition. Therefore it is necessary to emphasize pluralism and inclusion. Without that, we are stuck in religious exclusivity, which not only creates interreligious conflicts but can also cause conflicts within the religions.”

Perhaps more instinctively than purposefully, on the same day, Turkey’s President Abdullah Gül expressed the same concerns, but in a more obvious rather than academic manner. As interpreted by Today’s Zaman, he warned the Muslim world of the possibility of facing the darkness of the Middle Ages as Europe once did if interest-based beliefs are combined with sectarian identity politics following the Arab Spring. Delivering the keynote speech at the İstanbul Forum organized by the Center for Strategic Communication (STRATİM), President Gül stressed that no country, society or sect will benefit from such an era of “new troubles as a result of regional rivalries.” I am not aware of it if any other politicians or scholars have so bluntly called such intra-civilizational clashes a “disaster scenario” that would be worse than a clash of civilizations.

Greater need for dialogue

Speaking in the newly opened Gazi Husrev-Beg Library on Muslim-Christian dialogue in the 21st century, Professor Esposito further elaborated on the above-cited thesis, stressing that “the dialogue itself is not enough if it doesn’t lead to action.” In that case, it is a waste of time because there were many talks, arrangements and agreements between religious leaders in the past, “but they were put aside,” he said. Due to broad global communications, the need for dialogue has become even greater now if we want to avoid violence and conflict. He said, “In the era of the globalization of communications, religions and travels, everybody should respect others. Religious leaders should educate future generations to understand the richness of diversity that exists in their multi-ethnic societies.” To avoid religious amnesia, he stressed, “Muslims should follow in Islamic reformers’ footsteps and Christians those of their Christian reformers.”

Being aware in advance of controversies that had been spreading about Esposito for decades in academic circles, I had a chance to evaluate them closely, participating in a pleasant, intimate luncheon and two-hour-long conversation organized by the Sarajevo Center for Advanced Studies (CNS), led by Ahmed Alibasic, a young professor at the Faculty of Islamic Sciences.

As expected, the main subject was the Arab Spring, but we discussed various issues, including the Bosnian political impasse and dysfunctional state structure imposed by the Dayton Accords. Professor Esposito gave a new interpretation and touch to his old ideas, stressing that “we live in a smaller and smaller world in which there are many more Muslims everywhere, including the USA. … People should choose what to believe and no religion can claim a monopoly on God. … We need not exclusiveness, but pluralism, even inside religions. … Lectures of hate separate people. … Islam doesn’t need to be reformed; Muslims’ mindset should be reformed. … In today’s world of global terrorism, everybody is vulnerable.”

We also discussed positive and negative connotations of the terms Islamist and Islamization. When questioned by some young Bosnian Islamists if political Islam is being defeated by developments in the Middle East, he replied that the Muslim Brotherhood is losing, but political Islam is not dead. It should adopt new forms of expression and action.

Regarding developments in Egypt, Esposito clearly criticized the toppling of the first democratically elected government in Cairo, but also emphasized that former President Mohammed Morsi “was making mistake after mistake.” In his view, the present rule might last longer than expected. It has strong support from the conservative Arab countries and the US, and the West in general will accept this new reality.

‘Apologist for Wahhabi Islam’

I didn’t find any particular reason why he has been so criticized for “cozy ties with radical Islamists” by some other Western scholars, some of whom he has even mentored, in Esposito’s approach to Islam. Accusing him of being an “apologist for Wahhabi Islam,” for example, Stephen Schwartz has said, “His work has provided an unremitting ‘explanation’ that amounts to a committed defense of radical, rather than traditional, Islam.” Being a pious Catholic by virtue of his education, it is no wonder that Esposito sees in atheism an enemy to all religions and that he is not especially praised by liberal and leftist scholars. However, he probably didn’t need, besides his other prestigious titles, to become a founding director of the (Saudi) Prince Alwaleed Bin Talal Center for Muslim-Christian Understanding.

In fact, I am now more convinced that Esposito is not only a very prominent scholar of Islamic sciences but one who is more listened to and appreciated than some other greater Islamic scientists and philosophers, such as Seyyed Hossein Nasr, for example. In other words, Esposito is a Christian, plus an American scholar and thus has more influence than Nasr on the Western and American intellectual as well as official circles. More than Edward Said might have had, because though he was a Christian, he was an Arab and a Palestinian. At the same time and with the same motivations, Esposito is more targeted for his alleged partiality toward Islam, particularly due to his acknowledgment that radicalism exists in all “Abrahamic religions,” including Judaism and his support for the Palestinian cause.

Esposito doesn’t pardon his critics either, accusing them of Islamophobia. Having some of them in mind, such as Daniel Pipes, he wrote recently: “They do the same thing with the term Islamist; I say that Islamists can be mainstream or violent. They say that primarily they are violent and the mainstream ones are wolves in sheep’s clothing. It’s about the use of terminology and it reflects a radicalized view. They call me names because they are frustrated that I am not a Muslim and many of them, if not all, happen to be Jewish, but if I say this, that would be seen as unprofessional and racist, but it shows how politicized we have become.”

All in all, the phenomenon of Esposito is now becoming clearer to me. As a born linguist, I solved the problem of pronouncing his family name and its meaning as well. He confirmed that it is pronounced incorrectly even in America, putting the accent on the second syllable, instead of the first one as his grandmother did, who was brought to Brooklyn from a village near Napoli. In Italy, “esposito” means a kind of orphan.

I also found in his explanations of dialogue between religions a formula for compromise. Before, I was not sure if one of my Turkish friends and colleagues was right when asserting that such dialogue is impossible due to the antagonistic nature of all religions. John Louis Esposito helped me, when he said in Sarajevo that a dialogue between religions is useful only if it is critical and followed by activity, not by “wasting time.”

*Hajrudin Somun is the former ambassador of Bosnia and Herzegovina to Turkey.

Keywords: Bosnia and Herzegovina, John Louis Esposito, University of Sarajevo, Al-Wasatiyya Center for Dialogue